Overview

Emergency situations and forced displacement often increase the exposure of children and their families to a wide range of risks, including violence, abuse, and exploitation. These have life-long, devastating impact on the lives and development of children. Family and other social and community support networks are often weakened, and livelihoods and access to basic services such as education disrupted.

The protection of children is a longstanding global priority for UNHCR. It is governed by complementary and mutually reinforcing international legal and policy frameworks including International Humanitarian Law, Refugee Law, and International Human Rights Law, particularly the Convention on the Rights of the Child. UNHCR’s commitment to protecting children is not only a legal imperative, but also an operational commitment. It contributes to ensuring a better future for children, their families, and communities. The international humanitarian system recognizes child protection is a life-saving priority. Child protection prevention and response mechanisms must be established from the start of an emergency, or children's lives, safety and well-being will be put at risk. The most important outcomes of child protection in emergencies are to prevent violence, abuse, and exploitation, and to ensure displaced children’s access to protection and other essential services.

Relevance for emergency operations

In UNHCR-led emergency operations, preventing and responding to the multiple child protection risks from the outset is critical. When child protection is not well integrated into the overall operational response, protection risks for children may go unidentified and unaddressed. Emergency responses that do not adequately take into account and adapt to the specific experiences and protection risks of children of different age, gender and diversity characteristics can exacerbate risks or result in new harm to children. As such, UNHCR must continuously monitor and analyse the nature and scale of risks to children and the protective factors and develop a holistic response to address these risks. Child protection programming in emergencies must build on existing assistance and protection services and community-led protection mechanisms and support those that have been disrupted by the emergency. National child protection systems may be stretched or not functional during the emergency – as such, supporting national authorities to provide protection to children during emergencies should remain an integral part of UNHCR’s child protection response. Where such systems are unable to respond to the nature and/or scale of the emergency, UNHCR and partners should provide child protection services for children at risk. UNHCR should also work with communities, which often rally to support and protect children and their families during emergencies. UNHCR should integrate child protection in responses from the earliest stage of an emergency and together with partners work to urgently scale up child protection programming.

Main guidance

Child Protection objectives during emergencies

The goal of child protection programming in emergencies is to ensure that children of different age, gender and diverse characteristics are safe and protected and to prevent harm to children.

Priority child protection objectives during the first phase of an emergency include:

- Establishing well-coordinated interagency child protection prevention and response programmes.

- Identifying children at risk and ensuring they receive child protection services, including through implementation of Best Interests Procedure.

- Supporting children, families, and their communities’ efforts to protect children.

- Supporting the national child protection systems to be accessible and able to respond to the specific needs of forcibly displaced and stateless children from the outset.

- To give girls and boys access to child-friendly protection procedures, including reception, registration, asylum procedures and other legal procedures.

Children at Risk

The UNHCR ExCom Conclusions, No. 107 of 2007 recognises that wider environmental factors and individual risk factors, particularly when combined, can put children in situations of heightened risk. During emergencies and forced displacement children are at increased risks of violence, abuse and exploitation, and separation from their families. Violence and exploitation occur in the family, in communities, schools and institutions, and online and these risks can be physical, emotional or sexual (see also sexual exploitation and abuse). Child protection risks exist in all forcibly displaced settings and are largely predictable (see UNHCR’s analysis of Child Protection data from 2015 to 2021). In emergencies, children experience or are at risk of experiencing separation from parents and caregivers; physical and emotional abuse and neglect; sexual violence, sexual exploitation, and child marriage; mental health and psychosocial distress; exclusion and discrimination, trafficking, smuggling, and sale of children; illegal or inappropriate adoption; child labour, particularly worst forms of child labour; dangers and injuries; detention; and association with armed forces and armed groups. As they may move alone or with their families across multiple borders in search of safety, children may face refoulement, lack access to child-friendly asylum procedures and may experience immigration detention. It is important to remember that children often experience a combination of these risks, especially during emergencies.

Lack of access to child-friendly protection procedures, including registration and Refugee Status Determination, can lead to children not being identified and registered. In the case of refugee children, they may not be able to exercise their right to seek asylum and thus they may be refouled and returned to situations of danger and persecution, or they may be put in a position where they are easily exploited by adults.

Key steps

a) Analysis of child protection needs and capacities and developing a coordinated response

- Conduct desk review to identify child protection risks and protective factors, stakeholder capacities, and gaps in the child protection response, but remember that risks for children are prevalent even if there is a lack of comprehensive data.

- Incorporate child protection questions into the Needs Assessment for Refugee Emergencies (NARE) and Multi-Cluster/Sectoral Initial Rapid Needs Assessments (MIRA) (within 1 – 3 weeks), as well as in UNHCR-led protection monitoring (making use of the Protection Monitoring Toolkit - accessible to UNHCR staff only). Coordinate with protection and child protection actors for a comprehensive protection assessment and analysis (within 4-6 weeks, ongoing as required) and involve children in assessments.

- Assess the role and the capacity of the national child protection system and the degree to which displaced children of different age, gender and diversity backgrounds can access and benefit from these. This should include access to services, including national case management and alternative care systems. Refer to the UNHCR-UNICEF Inclusion Toolkit: Refugee Children in National Child Protection Systems.

- Support interagency mapping of child protection stakeholders (authorities, civil society, international organisations), and their technical and operational capacities and identify key gaps to be addressed by UNHCR and partners.

- Review UNHCR’s child protection capacity and determine the need for dedicated child protection staff. Depending on the identified capacity needs, submit request for deployment of child protection personnel (internal deployment mechanisms or Standby Partner deployments).

- In collaboration with relevant child protection actors, assess and address learning needs of UNHCR workforce, government staff, community volunteers, and partners.

- Based on the above information, develop UNHCR’s child protection response to the emergency (see below) with appropriate resources and funding for child protection programming by UNHCR, and include these in emergency appeals, response plans (e.g., RRP or HRP), UNHCR operational budget, staffing plans and strategies.

b) Programming for Child Protection

- Based on the rapid assessments and subsequent comprehensive assessment, update or develop a child protection situational analysis as part of the overall protection analysis.

- Within the Multi-functional Team, ensure that the operation’s capacity on child protection, child protection stakeholder presence, availability, scope, and other context-specific parameters are taken into consideration when identifying child protection strategic priorities and partnerships.

- Ensure child protection strategy, budget requirements and workforce needs are well integrated in the operational response plan as part of the overall protection response strategy. This includes selecting the child protection Outcome Area in COMPASS at the outset, and ensuring output, outcome statements and indicators that reflect the emergency context.

- Ensure child protection monitoring is integrated within the emergency monitoring and evaluation plan.

- Refer to the Programme Handbook on Partnership Agreements in Emergencies (accessible to UNHCR staff only) for further guidance.

c) Prevention of Risks for Children

- Together with children and their communities identify areas and actors that pose risk and causes of risks. Work with families, communities, and national authorities, including national or local police where appropriate to address the most common risks and implement priority actions to mitigate harm for children.

- Put in place immediate safety and security measures to keep children safe. These can include policing, safe, and supervised areas for children, and emergency lighting at displacement sites, and supporting children’s access to safe education.

- Develop and disseminate information to children and families on how to stay safe and mitigate risks in a format that is accessible, inclusive, and gender sensitive. Provide information on access to services and child protection. Make all information child-friendly, as access to information helps to prevent protection risks for children. (See section 6.1. Arrival and Reception in the Technical Guidance: Child-Friendly Procedures).

- Integrate child protection considerations into all response sectors to ensure safe and equitable access for children and their families, and provide support to ensure sectoral response are child-friendly and adapted to children’s age, gender and diversity characteristics to address risks, mitigate harm and ensure their wellbeing, including through ensuring child participation, child-friendly communication and accountability to children. Provide support to other sectors to ensure that children are safe and protected in education, cash transfers, livelihoods, and food security support the most vulnerable children and households, integrating violence prevention, child protection and psychosocial support into health and nutrition programmes, and adapting WASH programmes to be accessible and safe for children.

- In collaboration with UNHCR GBV workforce and partners within coordination forums (GBV sub-sector or GBV AoR), ensure that measures to prevent sexual violence and child marriage address the specific needs and rights of children (for example, by identifying risk factors specific to children).

- Put in place measures to prevent family separation during arrival, relocations, and evacuations. For instance, making sure families are kept together, ensuring screening procedures are in place before moving/transferring families, and provide information about times, routes and destination to families and children. Ensure that assistance procedures do not encourage deliberate separation (for example by targeting unaccompanied and separated children or encouraging families to split in order to receive additional assistance).

d) Child-friendly Protection Procedures

- In refugee situations, monitor children’s access to territory and asylum procedures and advocate with and assist relevant stakeholders to ensure access to and appropriateness of procedures.

- Establish and disseminate referral pathways with up-to-date information on services and contact information at arrival points, reception, and registration points.

- In refugee situations, provide guidance and training to border officials, reception, and registration personnel as well as other frontline workers in refugee, IDP and mixed settings on protection of children, safe identification, and referral of children at risk and communication with children.

- Ensure spaces in which protection procedures such as registration and RSD are conducted, are child-friendly, including providing communication material and information that are accessible to children of different ages and abilities, including for children with disabilities.

- Include clear guidelines and screening questions in emergency registration procedures that will identify children at risk (the prioritisation criteria included in the operation’s Best Interests Procedure (BIP) SOPs can serve as a guidance).

- Ensure staff assigned to Protection Desks have expertise on child protection, including on identification, quick assessment, and referrals to specialised child protection actors for follow-up support.

- Develop and disseminate at all sites where children arrive, transit, and stay child-friendly information on services for children including child protection services and procedures. Consult children on the type and format of the information to be developed and engage children and their communities in their dissemination.

- Monitor and report on child protection issues and violations through relevant mechanisms including protection monitoring. Where the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism (MRM) operates under Security Council Resolution 1612, contribute to the monitoring and report on grave violations against children in countries. See Technical Note on UNHCR's Engagement in the Implementation of the Protection Mechanisms Established by Security Council Resolutions 1612 and 1960 (MRM and MARA).

e) Child Protection response services and supporting national child protection systems

Identification and referral

- Train frontline sectoral staff and communities on safe identification and referral of children at risk, including to child protection actors/focal point for Best Interests Procedure (BIP). Remember, not all children at risk will require BIP, but instead it may be adequate for children to be referred to a specific service to address their needs. However, when in doubt children should be referred to the child protection actor/focal point.

- Disseminate referral pathways amongst frontline staff, children, families, and communities. Ensure information about available services are disseminated to children in a format that is child friendly.

- Train multi-sectoral services providers to safely identify, refer children at risk to existing child protection and other sectoral services and to provide child-friendly services to children at risk in their sector.

Best Interests Procedure (BIP)

- In refugee settings, where national case management is not available, accessible, or inclusive, set up Best Interests Procedure (BIP) to respond to the protection needs of individual refugee children at heightened risk in accordance with UNHCR’s BIP Guidelines. See also Checklists on BIP in Emergencies in the BIP Toolbox.

- Determine the scope and scale of BIP required in the emergency, identify a partner to implement BIP or assess and strengthen the capacity of the existing partners. Develop interagency plan to scale up Best Interests Procedures as rapidly as possible.

- Develop and adopt Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for the BIP, in consultation with stakeholders; where SOPs are in place, take steps to update these to better respond to the emergency context. The update may be in the form of an annex to the existing SOPs. SOPs should include prioritisation criteria, as well as appropriate services and actions for children with different child protection concerns. For guidance on developing SOP for BIP, see the UNHCR BIP SOPs Toolkit.

- Train (accessible to UNHCR staff only) relevant UNHCR, partner and government staff on the BIP. Note that if partners are conducting quality child protection case management, they do not need to change their practice, they only need to be trained on the procedural elements that are necessary for refugee and asylum-seeking children – e.g. the Best Interests Determination (BID).

- Ensure Best Interests Assessment (BIA) forms are translated into relevant languages where appropriate so that the form can be used easily by child protection staff. The BIA forms can be contextualised; the only requirements are that the child should be assessed by a qualified member of staff and that the assessment must be documented. Where possible, reduce the potential for additional data entry burden on child protection staff, by implementing or making available digital Information Management System for data entry.

- Establish or strengthen Information Management System for case management as soon as possible. UNHCR staff managing refugee child protection cases should wherever possible, use the CP module of proGres, while partners may use the Primero CPIMS+ (if used).

- In refugee settings, UNHCR should aim to establish BID panels within 3–4 months. (See Chapter 5.2.2 of the UNHCR BIP Guidelines for guidance). Before a BID panel is established, create a process for dealing with urgent cases. This can include using an existing national BID panel if appropriate or convening focal points with child protection expertise on an emergency basis. A simplified BID procedure can also be used (see Chapter 5.3 of the UNHCR BIP Guidelines for guidance).

- Develop a monitoring plan working with partners. This should include reviewing the trends of child protection issues facing children and the quality and scale of the response. (See Chapter 3.4.4. of the UNHCR BIP Guidelines for guidance and indicators). When required and based on monitoring findings, undertake additional training for the workforce, and make adjustments to the SOPs and tools used in BIP.

- In IDP settings, UNHCR should advocate for the establishment of child protection case management – see UNHCR child protection operational guidance for more information (upcoming).

Protection, care, and reunification of unaccompanied and separated children

- For unaccompanied children, in cooperation with national child protection authorities identify a range of alternative care options for children in different situations or assess the care arrangement if the child is in the care of an unrelated adult/family. Options are likely to include foster care and supervised independent living. Institutional care should be a last resort and for the shortest possible time. (See Interagency Alternative Care in Emergencies Toolkit). Siblings should not be separated when establishing alternative care.

- For separated children, with partners, support assessment of the care arrangement and provide support to existing arrangement, and where it is not in the child’s best interests, support provision of alternative care.

- Support or establish tracing activities (community-based tracing mechanisms, listening posts, children's desks, phone calls, progress searches, etc.) for unaccompanied and separated children. Coordinate with ICRC and national Red Cross/Crescent Societies or other engaged partners.

- Decisions regarding family tracing, reunification and alternative care should be based on each individual child’s best interests.

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS)

- In coordination with MHPSS actors, train UNHCR, partner and government staff and community networks on basic psychosocial support skills.

- Provide MHPSS through BIP.

- Support new and pre-existing group-based community MHPSS activities for children (See below section on Support to children, families, and communities to protect children).

Birth Registration

- Coordinate with health centres to ensure that birth notifications are issued for new-born children and support civil registration authorities to provide access to birth registration.

- Provide information to families about procedures and importance of birth registration. Include information about children’s birth in proGres.

Working with National Authorities

- Review the national legal and policy frameworks relating to children and child protection, and identify the key national ministries, departments, and authorities responsible for protecting children, as well as national standards and services on child protection. This should include an evaluation of the extent to which national and legal framework and services are inclusive and accessible to including refugee and/or IDP children.

- Establish contact with the relevant national child protection actor, and their representative in the operational area. Determine the extent to which the national child protection authorities are part of the national emergency response and coordination mechanism. Where national child protection authorities are not part of the emergency response, including coordination, advocate with coordination focal points for this inclusion.

- Involve national child protection authorities in assessments, response planning, implementation and monitoring of child protection programmes wherever possible. Ensure national child protection authorities are part of the preparation for post-emergency phase.

- Ensure capacity development on protection and programming and funding for national authorities include national child protection actors. Include national child protection workforce in child protection trainings.

- Support national systems and work towards the inclusion of forcibly displaced and stateless children. Humanitarian child protection services must completement and not duplicate national child protection services.

f) Support children, families, and communities to protect children

Children

- Support children though group activities that build children’s life skills for protection, psychosocial well-being, and participation. Ensure that age and gender-sensitive activities are developed and implemented for teenagers. This may include child friendly spaces, sports (see the Sport for Protection Toolkit), and reading, arts and crafts groups. Consult children to ensure programmes meet children’s needs and preferences.

- Provide children with information on positive coping mechanisms, protection, their rights, and services.

Families

- Promote caregivers’ mental health and psychosocial well-being and strengthen their capacity to protect children. This can include family strengthening and parenting skills programmes with a focus on address risks for children within their families.

- Disseminate key messages to promote mental health and psychosocial well-being and protection of children and their caregivers, as well as how they can access services.

Communities

- Supporting community-level efforts to protect children, such as training and mentoring for community-based actors on the protection of forcibly displaced, community-led action and community outreach on the care and protection of children.

- Work with partners to develop or adapt existing social and behaviour change initiatives to promote protective behaviours and norms and address harmful norms that contribute to child protection risks into the emergency response.

g) Coordination for Child Protection

In refugee situations

- UNHCR is the lead agency within the United Nations system accountable for supporting authorities, coordinating and providing international protection and assistance, seeking solutions and advocating on behalf of refugees. UNHCR must ensure child protection is effective coordinated.

- Work with the Protection Sector and child protection actors including authorities to determine how to coordinate interagency child protection responses by assessing the scale, complexity, the capacity of the government and the operational context. Where a child protection sub-working group is established, UNHCR should co-lead with the government if possible, and if not with another child protection actor. Please refer to the Refugee Coordination Model Guidance and to the Terms of Reference for the Child protection Sub-Sector Working Group.

- Ensure effective facilitation of the coordination mechanism through developing/customising Terms of Reference (TORs), work plan/ strategy.

- Lead the drafting of the child protection component of UNHCR protection strategy (with analysis and advocacy), the child protection elements of the Refugee Response Plans, country protection and solution strategies and other relevant interagency process.

In internal displacement situations

- UNHCR should actively participate in the country Child Protection Area of Responsibility (CP AoR) and contribute to the coordination and implementation of child protection programming.

- UNHCR should configure its strategy (accessible to UNHCR staff only), programming and interventions in child protection also based on the existing resources of the CP AoR, working on complementarity and addressing gaps in the interagency child protection response.

Post emergency phase

Child protection emergency response should focus on addressing the immediate, medium, and long-term protection risks from the outset. Simultaneously, plans and programmes should also consider the post-emergency child protection needs, based on context. As not all pre-existing risk and newly emerged risks may be addressed during the first phase of the emergency response, UNHCR should work with the national child protection actors and partners to ensure on-going prevention and response activities. This should be done while working to strengthen national child protection capacity, empowering children, and their communities, establishing links to development programmes and approaches, and incorporating child protection considerations into durable solutions. As part of the transition to post-emergency phase:

- Ensure child protection is clearly reflected in the operation’s multi-year plan.

- Strengthen capacity of government, UNHCR and partner staff, including in cooperation and coordination with other Child protection specialised agencies, especially UNICEF.

- Advocate for sustained funding to national child protection actors and to strengthen the national child protection system.

- Strengthen local child protection capacities, and where available strengthen child protection capacity of organisations led by displaced communities, including by using agile UNHCR funding tools (e.g., Small Grant) and advocating with donors to support the most effective grass-root organisations providing child protection programming.

- Review the coordination arrangements, those led by UNHCR in refugee situations, or in the context of an interagency review of the Clusters, and determine whether any changes are required (e.g., change the type of coordination mechanism, establish additional coordination mechanism at the sub-national level, etc.).

Child Protection Prevention and Response programming

Analyse child protection needs and capacities.

Develop plan for child protection programming and advocacy; identify human and financial resources for scaling up child protection programming.

Establish or strengthen child protection coordination and integrate child protection into protection coordination mechanism.

In partnership with other child protection actors, assess and support national child protection systems and services.

Establish referral child protection pathways and train frontline workers on safe identification and referral.

Establish prevention activities, including evidence-based child protection programmes and mainstreaming child protection in protection and other sectors response.

Where gaps exist, provide services for children at risk including psychosocial support, BIP, alternative care, and family tracing and reunification. Update or establish child protection standard operating procedures.

Establish or expand partnership arrangements for child protection interventions.

Establish and implement a monitoring system for child protection risks and programming.

Standards

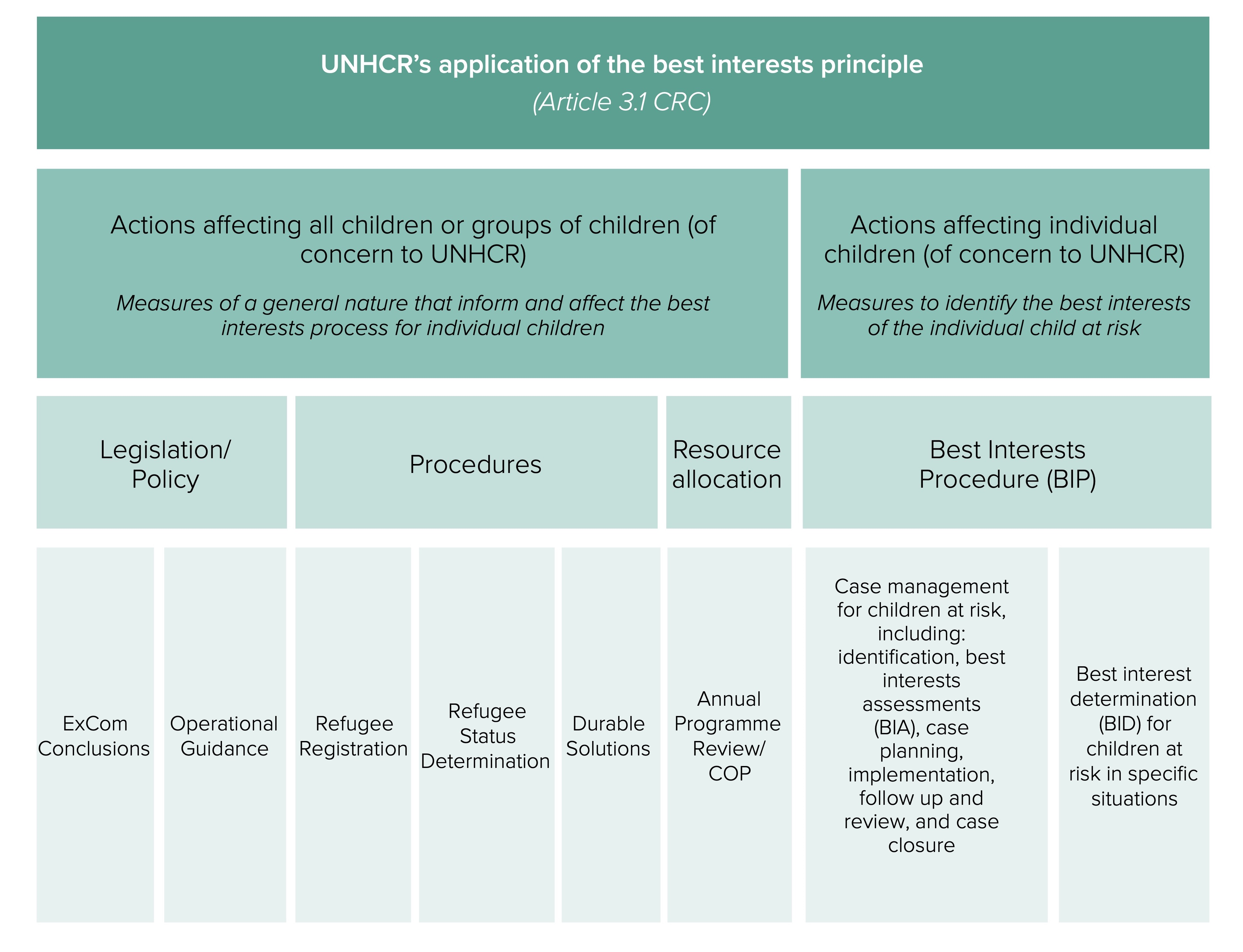

UNHCR's application of the best interests principle (Article 3.1CRC)

UNHCR seeks to ensure that children’s best interests are a primary consideration in all its actions affecting children or groups of children as well as actions affecting individual children (see table below).

Minimum Standards for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action

Core principles and standards for child protection work (see diagram below). Although they were not developed specifically for refugee situations, and do not address specific issues relating to children in refugee procedures, such as registration, Refugee Status Determination (RSD), or durable solutions, the principles and standards are applicable to all settings and should guide UNHCR's child protection emergency response. The CPMS complement UNHCR-specific child protection policy and guidance, for example, the UNHCR Child Protection Policy, on the 2021 BIP Guidelines and the Technical Guidance: Child-Friendly Procedures.

State responsibility

UNHCR supports States as the primary actor responsible for the protection of forcibly displaced and stateless children and the provision of non-discriminatory access to services to all children under their jurisdiction, regardless of their legal status or other age, gender, and diversity characteristics. Promoting and supporting children’s access to national child protection systems are a key part of UNHCR’s child protection work and should be an integral component of the emergency response.

Prevention and early intervention

Protection of children cannot wait. It must take early action where children are at risk, in order to mitigate those risks and prevent.

Participation

Participation and inclusion of children in all stages of the emergency response cycle should be supported. Children should be recognised and supported as active agents in their own protection and recognize and build on children’s capacities and resilience.

Child-friendly communication and accountability

In line with the UNHCR Policy on Age, Gender and Diversity, all communication with children must be child-friendly. This includes putting in place child-friendly accountability mechanisms including providing children with child-friendly information on their rights and services, ensuring that feedback and response mechanisms are child-friendly and adapting the emergency response strategies based on children’s views.

Partnership and mainstreaming

UNHCR engages and collaborates with State and other actors to protect children, integrate child protection in all programming as part of the humanitarian response, and identify and address critical gaps and needs in a coordinated manner.

The Inter-Agency Guiding Principles on Unaccompanied and Separated Children

These principles provide definitions and key standards and principles for preventing and responding to family separation, and on working with unaccompanied and separated children.

Policies and guidelines

Links

Main contacts

In this section:

Let us know what you think of the new site and help us improve your user experience….

Let us know what you think of the new site and help us improve your user experience….